Amenhotep IV

Amenhotep IV, whose name means Amun is Satisfied, lived during the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt and probably had a very nice life. His father, Amenhotep III, was pharaoh. His mother Tiye was his father’s Great Royal Wife, as opposed to being the son of a lesser consort, as his own father had been. He had an older brother, Thutmose, who died before their father, leaving Amenhotep IV in line for the throne when their father died in what Egyptologists believe was his 39th year of reign, 1353 or 1351 BC. Little else is known of his youth, but enough is known about his adult life to be sure Amun was anything but satisfied with this young man.

Big Changes Ahead

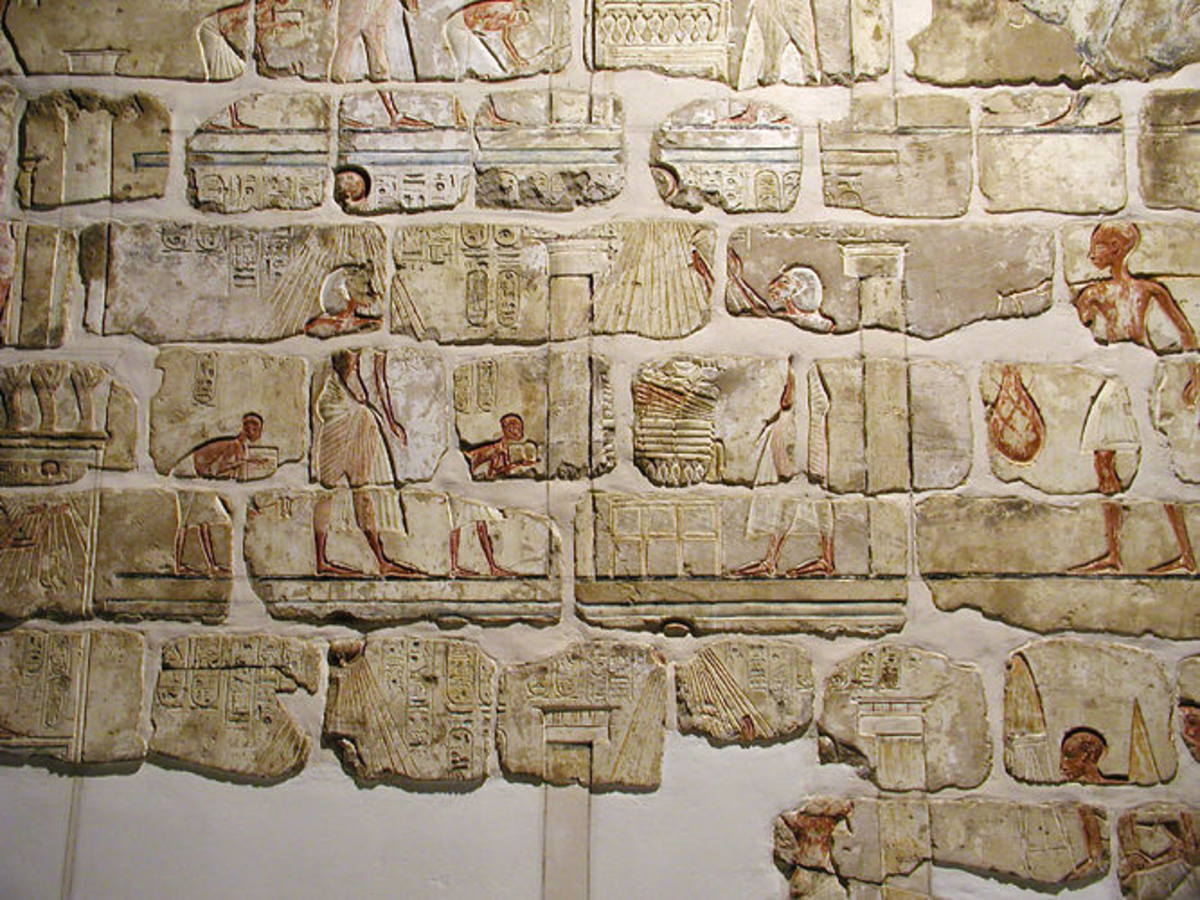

His reign started normally. He began building projects in Thebes, modern day Luxor. He had the temple of Amun-Re updated. Then he had a temple, called Gempaaten, built for the Aten. Little did anyone know, however, what this would lead to. We know little about this temple other than it was huge and oriented to the east, the direction of the rising sun. In the small section of wall that was salvaged, we can clearly see a glimpse of what was to come – the pharaoh worshiping the sun disc.

In the fifth year of his reign, he changed his name, moved the capital city out to the middle of nowhere and started a campaign that would result in the destruction of everything he built shortly after his death.

Exactly why Amenhotep IV changed not only his own religious beliefs but also those of his entire kingdom, may never be fully known, but many scholars believe that suggestions from his father led to the change. While the sun was always extremely important to the Egyptians, with the sun god Ra being the main national deity and father of the gods, an upstart local god from Thebes had started to grow in importance. During the rule of Ahmose I in the beginning of the Eighteenth dynasty, however, Amun became blended with Ra and the combined god Amun-Ra was really taking hold of the country.

The Hyksos, foreigners, probably from Canaan, had controlled portions of Egypt during the Seventeenth dynasty, and it was leaders from Thebes that removed them from the country. As a result, Thebes became the new capital city and Amum a new national god. Nine pharaohs and approximately 180 years later, the priests of Amun-Ra were wielding so much power that Amenhotep III warned his son that he would need to somehow lessen their authority or the pharaoh would eventually have no power at all.

One way Amenhotep IV could have reduced the power of the Amun-Ra priests would be to reduce the power of the god himself. In the end, he not only reduced the power of Amun-Ra, he eliminated him, along with all other gods, all together.

The pharaoh still believed in the power of the sun as the supreme life giving force, and his father had worshiped the Aten during his own reign. This is most likely the reason Amenhotep IV chose this god to focus his attention. Ra-Horakhty, Ra who is Horus in the Horizons, was now the number one god and would quickly become the only god to be worshiped.

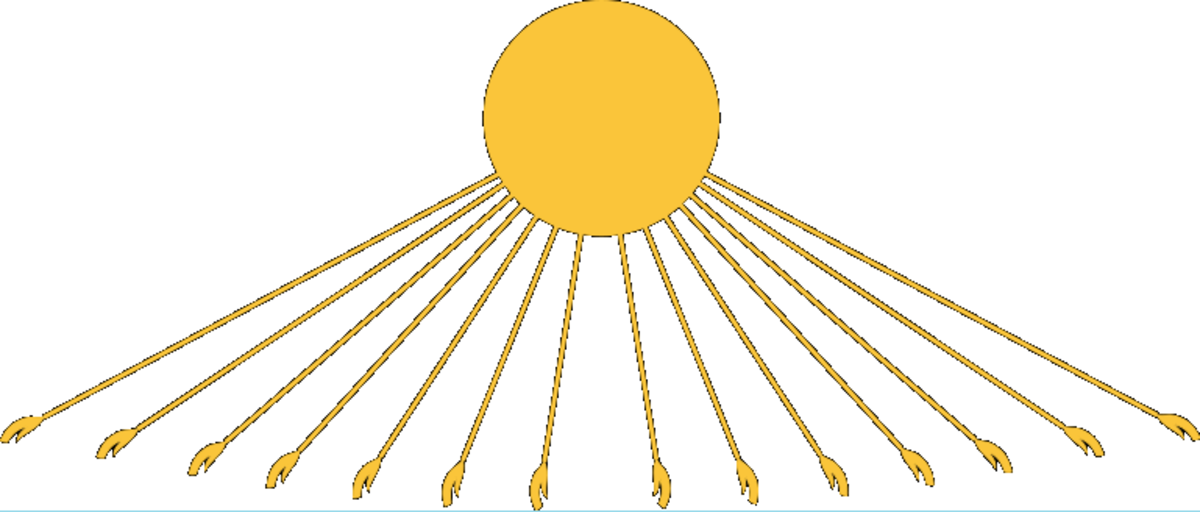

So who or what exactly was Ra-Horakhty? The god Ra had taken many forms during his worship. A longtime understanding of Ra was that he existed in three parts. Khepri-Ra was the morning sun, Khnum-Ra was the setting sun and Ra was the afternoon sun. Ra-Horakhty took all three of these and put them together as one. Joining Ra, the sun god, and Horus, the sky god, Ra-Horakhty (Ra-Horus-Aten) represented the sun during its entire trek across the sky. It was usually represented as a sun disc with rays of light shining down.

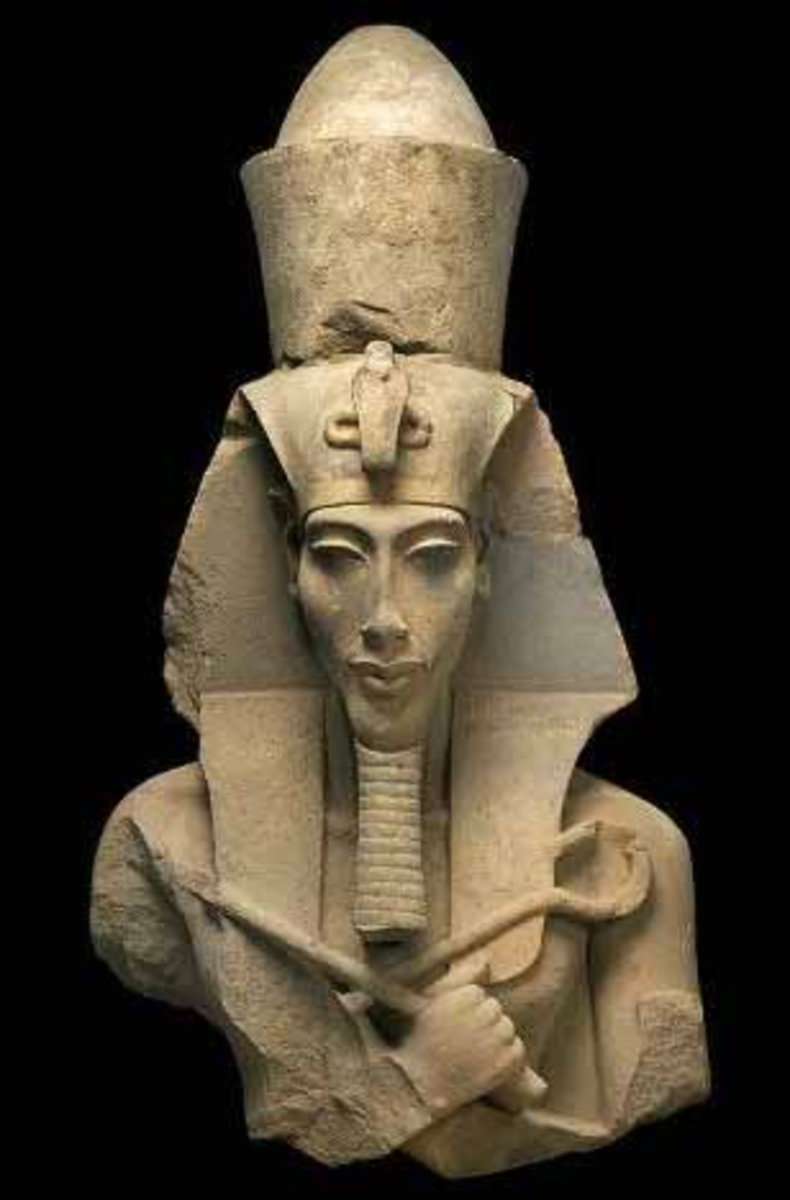

Amenhotep IV could no longer have a name that reflected a god he did not worship. For this reason, he changed four of his five official names to reflect his new beliefs. He now became Akhenaten, meaning Effective for the Aten. He also moved the capital city to Amarna, known as Akhetaten at the time. By taking the capital away from Thebes, essentially the home of Amun and a place with many temples to the other gods, he lessened the affect those gods would have on the daily life of his advisors. His new city, would become completely dedicated to the Aten, and moving the capital also removed the Amun-Ra priests from the seat of power, which is exactly what Akhenaten wanted to do.

Does this mean that Aknenaten forbid the worship of the old gods? Despite the common perception that this was the case, there were no writings to support the idea that anyone was executed for worshiping any god other than Aten. It seems that Akhenaten understood that it would take time to change something so ingrained in people as their religion, but the worship of the Aten was the only state sanctioned religion, and the only one practiced in public by Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti. To further support this theory, many of the advisors to Akhenaten maintained their original names that referenced other gods like Thoth, and artifacts for other gods like Horus, Bes and Taweret have been found in Amarna.

Toward the end of his life, Akhenaten did become more extreme with his beliefs. He claimed himself to be the son of the Aten. It was his contention that as Aten’s son, only he could communicate with the god, and only he could translate the word for his people. In the end, he would worship the Aten, and everyone else would worship him. Many have compared this relationship to that of God and Jesus Christ.

The Family of Akhenaten

More than any pharaoh before him, Akhenaten’s family was prominently displayed in the images of his time, and his great royal wife, Nefertiti, is by his side through everything. Some historians even went so far as to offer that she became a co-regent late in her husband’s reign, but that has become considered unlikely, though she did change her name to Neferneferuaten Nefertiti to indication her devotion to the Aten like her husband. It is still believed that she served as co-regent under the name Neferneferuaten during the beginning of her stepson, Tutankhaten’s, reign. In fact, some historians believe that her death in the young pharaoh’s third year of reign was the catalyst for the pharaoh’s own name change to Tutankhamun and the move of the capital back to Thebes.

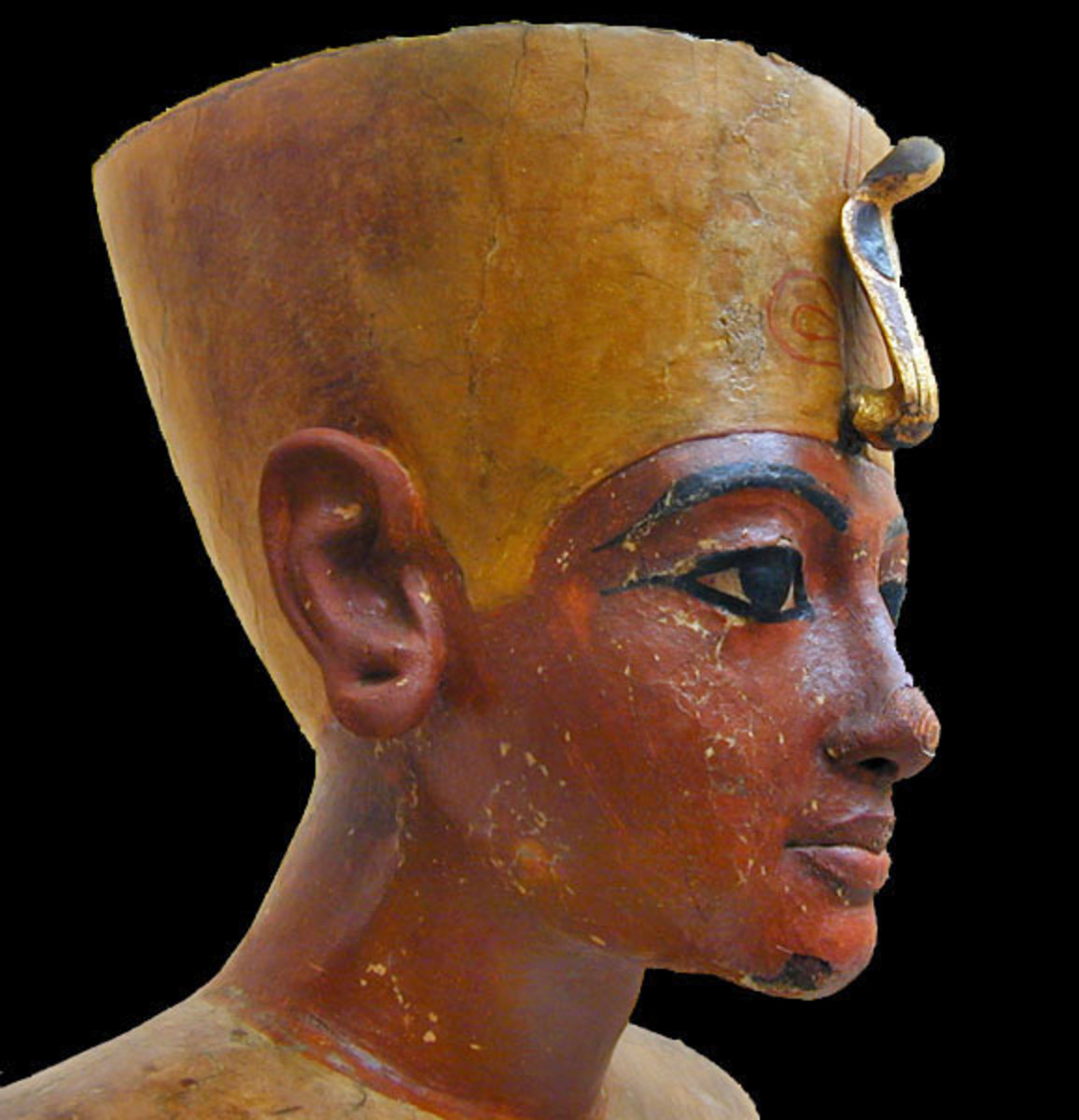

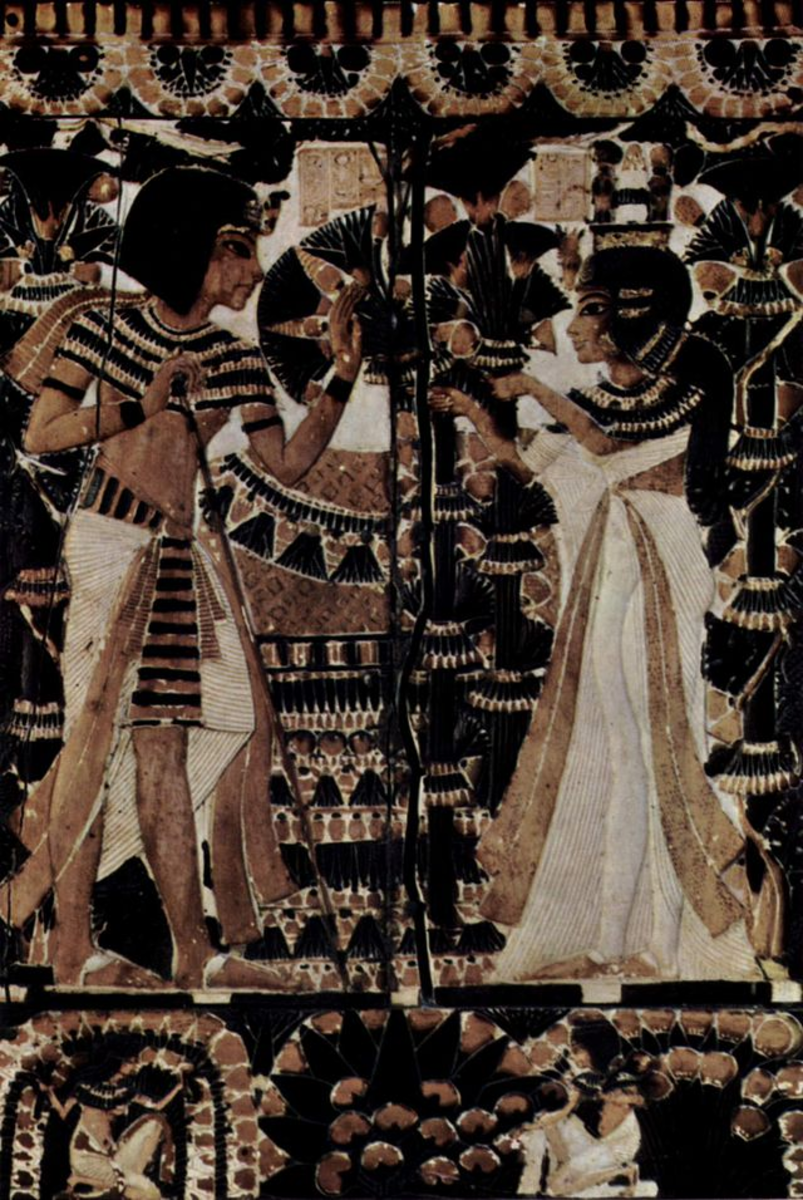

One thing to note about the artistic work done during Akhenaten’s reign is that it had more realism to it than any other period before or after. The pharaoh himself is always portrayed having an elongated head, a protruding chin, a potbelly and wide hips. He certainly did not have the perfect physique of say a Ramesses II or Thutmose III. His wife, too, had a more realistic looking, though extremely beautiful, face.

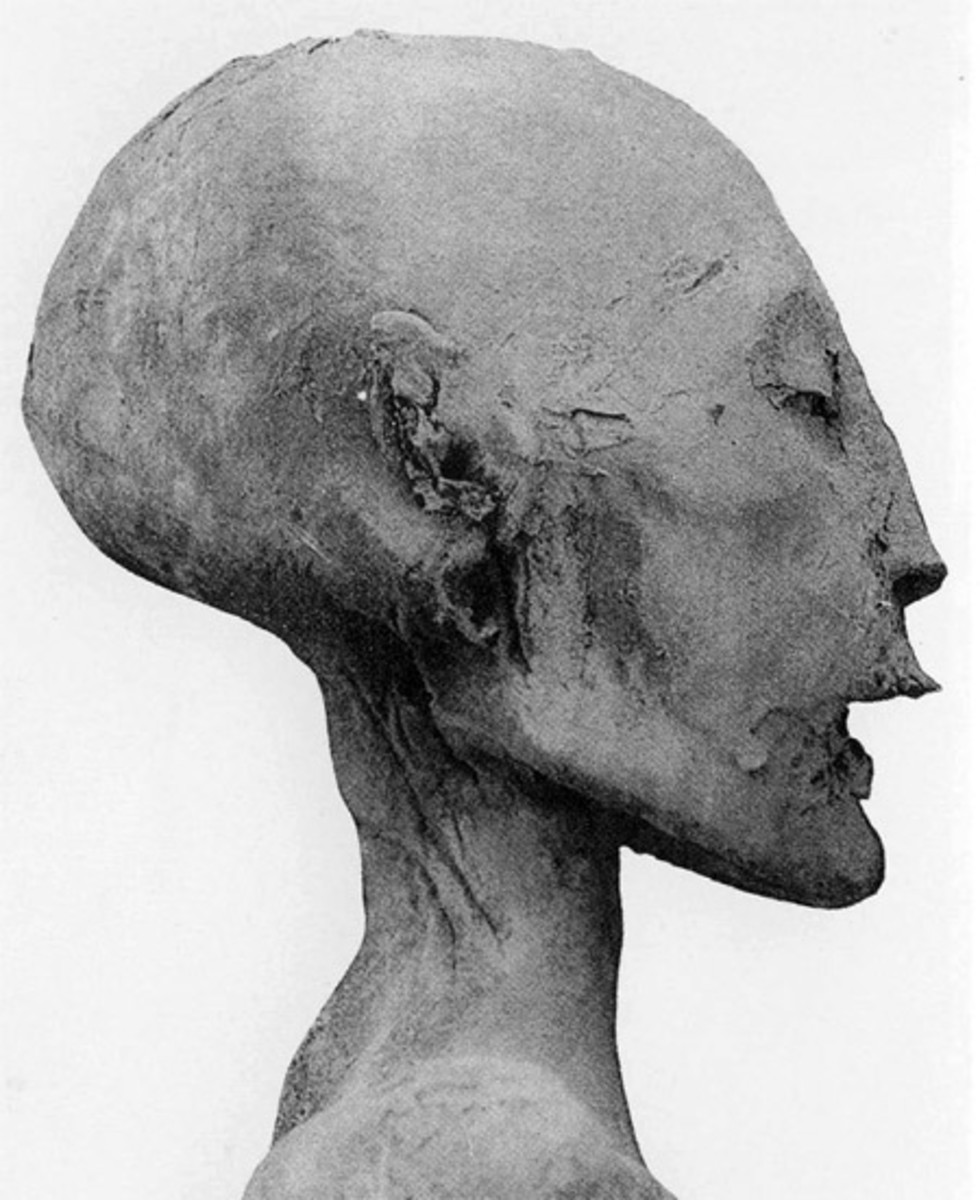

Many historians could not figure out why the pharaoh and his children, who were also shown with elongated heads, would be depicted this way. Some thought it was a way to show them in a connection to the Aten while others thought it might truly be the way they looked. Egyptologists were beginning to wonder if they would ever figure it out, as a specific tomb for Akhenaten was never found. In 2012, however, a mummy found in tomb KV55, was proven through DNA to be that of Akhenaten. The answer as to why the images appeared as they did was obvious. He truly did look that way.

Speculation as to medical issues that would result in this appearance have been considered with Marfan’s Syndrome coming the closest to explaining the deformations, however, DNA tests on Tutankhamun ruled out this disorder. Another good possibility would be homocystinuria in which the person has a genetic deformation resulting in amino acid issues.

Akhenaten and Nefertiti had six daughters, Meritaten, Meketaten, Ankhesenpaaten, Neferneferuaten Tasherit, Neferneferure and Setepenre. The pharaoh also had one son, Tutankhaten.

Based on DNA testing, it has been proven that Tut’s mother was a full sister to Akhenaten of which he had four. Her mummy has been located, but her name has not. Given the options of Sitamun, Henuttaneb, Isis and Nebetha my personal speculation would be Henuttaneb. This is because both Sitamun and Isis were raised to the status of Great Royal Wife to their father Amenhotep III, and it is speculated that Nebetah died young. In addition to this, Henuttaneb’s name has been found inside of a cartouche, which was reserved for only kings and queens. If she was a queen to her brother Akhenaten, this would not have been unusual.

If you refer back to the picture of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye at the beginning of the article, that is Henuttaneb standing between her parent’s legs.

Ankhesenpaaten, the daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti would become the Great Royal Wife of her half-brother Tutankhaten. Both would change their names to Ankhesenpamun and Tutankhamun respectively after the death of Nefertiti when they returned the country to the religious practices widely held before their father’s rule. Their only two children would result in stillborn daughters.

Following the Death of Akhenaten

After Akhenaten’s death, everything he tried to create began to fail. The first to rule was a man named Smenkhkare. Exactly who this was in relation to Akhenaten is not clear. He might have been a son, but this is not known for certain. He was married to Meritaten, Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s oldest daughter. He ruled for no more than one year.

Following Smenkhakare, Neferneferuaten ruled for two years and many believe this was Nefertiti herself. It is known for certain that this pharaoh was female. One epithet for this ruler was Anket-en-hyes which translates to Effective for her husband. As we also know that Nefertiti changed her name to include Neferneferuaten, it stands to reason that this was the wife of Akhenaten.

When Tutankhaten/Tutankhamun was old enough, he took the throne, but by all accounts he was young and sickly. Much of the control of Egypt fell to Nefertiti and/or two men who were high members of Akhenaten’s council, Ay and Horemheb. It may have been Tutankhamun’s weaknesses that led him to return the country to its former religious beliefs, as he may have been pressured by his council or feared it was the only way for him to survive. Tut managed to rule for nine years before his death in 1323 BC.

With the death of Tutankhamun, there was no male heir. Ay then became pharaoh. Many believe that he had been the driving force for Egypt since the death of Akhenaten. He was the son of Yuya, an influential member of Amenhotep III’s court and father of Queen Tiye. In addition to being the brother of Queen Tiye, Ay was the father of Nefertiti and, therefore, father-in-law of Akhenaten. He ruled for four years.

With the death of Ay, Horemheb took the throne. Horemheb had been the commander of the Egyptian military for both Tut and Ay, but now that he was pharaoh he set about changing things he had not approved of from the time of Amenhotep III’s death. Not only did Horemheb try to eliminate all traces of the time in Amarna, he also tried to eliminate all traces of the rule of Tut and Ay. It was his intention to have his rule begin at the time of Tutankhamun’s rule. Horemheb ruled for 14 years, but as he too had no male heir, he set about to select a replacement that would ensure a strong ruling family for generations to come. His choice was Ramesses I. With his death and the ascent of Ramesses I to the throne, the Eighteenth dynasty came to an end and the Nineteenth dynasty began.

Conclusion

The time of one god was over. Egypt went back to worshiping its many gods. The capital was back in Thebes, until Ramesses II moved it to Pi-Ramesses, and Amarna was just a bad dream that never really existed and no one in the future would ever know about. Except we do know all about it. We have been able to piece enough of what was destroyed back together and read between the lines. We can read the hieroglyphs and use DNA to determine relationships. We can also understand that many people of the time did not approve of the move Akhenaten made, especially Horemheb, but we can also see that if the heretical pharaoh had not made a move, it is quite possible that Horemheb himself never would have been pharaoh, as the position might have been eliminated by the priests of Amun. In the end, Egypt was none the worse for Akhenaten’s experiment, and it ensured that we would eventually see Ramesses the Great rule, though little of the thousand years of pharaoh after him would live up to the standards of the New Kingdom of Egypt.

This website was… how do I say it? Relevant!! Finally I have found something that helped me. Many thanks!

Heya i’m for the primary time here. I came across this board and I in finding It truly useful & it helped me out a lot. I am hoping to offer something back and help others like you helped me.

This piece of writing is in fact a pleasant one it helps new net viewers, who are wishing for blogging.

Thanks for your personal marvelous posting! I genuinely enjoyed reading it, you will be a great author.I will be sure to bookmark your blog and will eventually come back later in life. I want to encourage you to definitely continue your great posts, have a nice morning!

Woah! I’m really loving the template/theme of this website. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s very hard to get that “perfect balance” between superb usability and visual appeal. I must say that you’ve done a awesome job with this. In addition, the blog loads extremely fast for me on Internet explorer. Outstanding Blog!

I am extremely inspired together with your writing skills and alsosmartly as with the layout on your blog. Is this a paid subject or did you customize it yourself? Either way stay up the nice quality writing, it’s rare to peer a nice blog like this one these days..

Hi everyone, it’s my first go to see at this web site, and post is truly fruitful designed for me, keep up posting such articles.

An impressive share! I have just forwarded this onto a coworker who had been doing a little research on this. And he in fact bought me breakfast simply because I found it for him… lol. So let me reword this…. Thank YOU for the meal!! But yeah, thanx for spending the time to discuss this topic here on your web site.

It is appropriate time to make some plans for the future and it is time to be happy. I have read this post and if I could I wish to suggest you few interesting things or advice. Perhaps you could write next articles referring to this article. I want to read more things about it!

Thank you, I have recently been searching for information approximately this topic for a while and yours is the best I have found out so far. However, what concerning the conclusion? Are you positive about the source?

I visit everyday some sites and information sites to read articles, but this weblog provides quality based articles.

Helpful info. Fortunate me I found your web site accidentally, and I am surprised why this coincidence did not came about in advance! I bookmarked it.

I couldn’t resist commenting. Well written!

hey there and thank you for your information I’ve definitely picked up anything new from right here. I did however expertise a few technical issues using this site, since I experienced to reload the site a lot of times previous to I could get it to load properly. I had been wondering if your web hosting is OK? Not that I am complaining, but sluggish loading instances times will very frequently affect your placement in google and can damage your high quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords. Anyway I’m adding this RSS to my e-mail and can look out for a lot more of your respective interesting content. Make sure you update this again soon.

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz answer back as I’m looking to design my own blog and would like to know where u got this from. thanks a lot

Thanks for sharing such a pleasant thought, piece of writing is nice, thats why i have read it fully

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You definitely know what youre talking about, why waste your intelligence on just posting videos to your site when you could be giving us something enlightening to read?

I read this article fully about the comparison of latest and preceding technologies, it’s awesome article.

First off I want to say wonderful blog! I had a quick question that I’d like to ask if you don’t mind. I was curious to know how you center yourself and clear your thoughts before writing. I have had a difficult time clearing my mind in getting my thoughts out. I do enjoy writing but it just seems like the first 10 to 15 minutes are generally wasted just trying to figure out how to begin. Any suggestions or tips? Cheers!

I’m really enjoying the design and layout of your site. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more enjoyable for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a designer to create your theme? Excellent work!

I couldn’t resist commenting. Very well written!

Hello! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a collection of volunteers and starting a new initiative in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us useful information to work on. You have done a extraordinary job!

Everything is very open with a clear description of the issues. It was truly informative. Your website is extremely helpful. Thank you for sharing!

I’m not sure why but this website is loading extremely slow for me. Is anyone else having this issue or is it a problem on my end? I’ll check back later and see if the problem still exists.

What i do not realize is in reality how you’re now not really a lot more well-liked than you may be right now. You are so intelligent. You recognize therefore significantly in relation to this topic, produced me personally believe it from so many numerous angles. Its like men and women don’t seem to be interested unless it’s something to accomplish with Woman gaga! Your personal stuffs great. Always maintain it up!

Hi, I do believe this is an excellent web site. I stumbledupon it 😉 I’m going to return once again since I book marked it. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to help other people.

My relatives always say that I am wasting my time here at net, except I know I am getting knowledge every day by reading such good articles.

wonderful issues altogether, you just won a emblem new reader. What may you suggest in regards to your post that you simply made a few days ago? Any sure?

Fantastic beat ! I wish to apprentice at the same time as you amend your site, how can i subscribe for a blog web site? The account aided me a applicable deal. I were tiny bit familiar of this your broadcast provided shiny transparent concept

I have been surfing online more than three hours today, yet I never found any interesting article like yours. It’s pretty worth enough for me. Personally, if all webmasters and bloggers made good content as you did, the net will be much more useful than ever before.

Nice post. I was checking continuously this blog and I am impressed! Very useful information particularly the last part 🙂 I care for such info a lot. I was seeking this particular info for a long time. Thank you and good luck.

Ahaa, its good discussion regarding this article here at this webpage, I have read all that, so now me also commenting here.

It’s a shame you don’t have a donate button! I’d certainly donate to this superb blog! I suppose for now i’ll settle for book-marking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account. I look forward to brand new updates and will talk about this blog with my Facebook group. Chat soon!

Отборный частный эротический массаж в Москве база массажа

This information is priceless. How can I find out more?

I got this site from my friend who told me regarding this web site and now this time I am visiting this site and reading very informative articles or reviews here.

Thank you a bunch for sharing this with all folks you really realize what you are talking approximately! Bookmarked. Please also discuss with my site =). We will have a link trade contract among us

Hi! Quick question that’s completely off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My site looks weird when viewing from my iphone4. I’m trying to find a theme or plugin that might be able to fix this problem. If you have any suggestions, please share. Appreciate it!

Incredible quest there. What occurred after? Thanks!

Great article! This is the type of information that are supposed to be shared around the web. Disgrace on the seek engines for now not positioning this post upper! Come on over and seek advice from my web site . Thank you =)

Thank you for another informative blog. Where else may just I am getting that kind of info written in such a perfect approach? I have a venture that I am simply now operating on, and I have been at the glance out for such information.

This is a topic that’s close to my heart… Take care! Where are your contact details though?

A person necessarily lend a hand to make significantly articles I might state. This is the first time I frequented your web page and to this point? I amazed with the research you made to create this actual post incredible. Magnificent task!

What’s up to every body, it’s my first visit of this website; this website contains awesome and really fine stuff in favor of readers.

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact used to be a leisure account it. Glance complex to far brought agreeable from you! By the way, how can we keep up a correspondence?

Fine way of explaining, and good article to take data about my presentation subject matter, which i am going to convey in college.

What a data of un-ambiguity and preserveness of precious familiarity about unexpected feelings.

It is perfect time to make some plans for the future and it is time to be happy. I have read this post and if I could I want to suggest you few interesting things or advice. Perhaps you could write next articles referring to this article. I want to read more things about it!

What’s up, all is going perfectly here and ofcourse every one is sharing data, that’s in fact fine, keep up writing.

Hi there, I enjoy reading all of your article. I like to write a little comment to support you.

Have you ever considered about including a little bit more than just your articles? I mean, what you say is fundamental and all. Nevertheless just imagine if you added some great graphics or video clips to give your posts more, “pop”! Your content is excellent but with images and video clips, this site could certainly be one of the very best in its niche. Amazing blog!

Hi there to every body, it’s my first go to see of this webpage; this blog consists of awesome and in fact fine information in favor of readers.

This is my first time pay a visit at here and i am in fact impressed to read all at one place.

What’s up to all, how is all, I think every one is getting more from this website, and your views are pleasant for new people.

Hi Dear, are you in fact visiting this website regularly, if so then you will absolutely get nice experience.

You should take part in a contest for one of the highest quality sites on the net. I will recommend this blog!

I don’t know if it’s just me or if everyone else experiencing problems with your blog. It looks like some of the text on your posts are running off the screen. Can someone else please comment and let me know if this is happening to them too? This could be a problem with my browser because I’ve had this happen before. Kudos

It’s very simple to find out any topic on net as compared to books, as I found this piece of writing at this site.

I don’t even understand how I stopped up here, however I thought this submit was good. I don’t realize who you are however definitely you are going to a famous blogger when you are not already. Cheers!

Great goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you’re just too magnificent. I really like what you’ve acquired here, really like what you’re stating and the way in which you say it. You make it entertaining and you still take care of to keep it sensible. I cant wait to read far more from you. This is actually a terrific site.

Highly energetic article, I enjoyed that a lot. Will there be a part 2?

Быстровозводимые строения – это актуальные здания, которые отличаются высокой быстротой строительства и мобильностью. Они представляют собой сооруженные объекты, образующиеся из эскизно сделанных компонентов либо блоков, которые могут быть быстро собраны в месте развития.

Быстровозводимые здания цена под ключ обладают гибкостью также адаптируемостью, что дает возможность просто менять и модифицировать их в соответствии с запросами заказчика. Это экономически результативное и экологически устойчивое решение, которое в последние годы заполучило обширное распространение.

We stumbled over here coming from a different page and thought I might check things out. I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to going over your web page again.

Awesome! Its truly awesome article, I have got much clear idea concerning from this post.

Ahaa, its pleasant discussion concerning this post here at this blog, I have read all that, so now me also commenting here.

Nice blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A design like yours with a few simple adjustements would really make my blog shine. Please let me know where you got your design. Many thanks

Your style is very unique compared to other people I have read stuff from. Thank you for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I will just bookmark this page.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this web site before but after going through some of the posts I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I discovered it and I’ll be bookmarking it and checking back regularly!

This is very interesting, You are a very skilled blogger. I have joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your wonderful post. Also, I have shared your site in my social networks!

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz reply as I’m looking to design my own blog and would like to know where u got this from. thanks

wonderful issues altogether, you just won a emblem new reader. What could you suggest in regards to your post that you made a few days ago? Any sure?

What a stuff of un-ambiguity and preserveness of precious knowledge concerning unexpected feelings.

I am extremely impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your blog. Is this a paid theme or did you customize it yourself? Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it’s rare to see a nice blog like this one nowadays.

A person necessarily help to make seriously articles I would state. This is the first time I frequented your web page and thus far? I amazed with the research you made to create this actual post incredible. Wonderful task!

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in reality used to be a amusement account it. Glance complicated to far brought agreeable from you! By the way, how can we communicate?

Useful info. Fortunate me I found your site by chance, and I am surprised why this twist of fate did not came about in advance! I bookmarked it.

Excellent article! We will be linking to this great post on our site. Keep up the good writing.

Wow that was odd. I just wrote an very long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t show up. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyway, just wanted to say wonderful blog!

Truly no matter if someone doesn’t understand after that its up to other users that they will help, so here it occurs.

Excellent post. I was checking continuously this blog and I am impressed! Very useful information specially the last part 🙂 I care for such info a lot. I was seeking this particular info for a long time. Thank you and good luck.

My family members all the time say that I am wasting my time here at net, but I know I am getting knowledge everyday by reading such nice articles or reviews.

I’ve been exploring for a little bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts in this kind of area . Exploring in Yahoo I finally stumbled upon this site. Reading this info So i’m satisfied to express that I have a very good uncanny feeling I came upon exactly what I needed. I so much without a doubt will make certain to don?t put out of your mind this web site and give it a look on a constant basis.

Sweet blog! I found it while browsing on Yahoo News. Do you have any tips on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Thanks

Great post. I am going through some of these issues as well..

My relatives always say that I am wasting my time here at net, except I know I am getting experience daily by reading such good articles.

Wow that was strange. I just wrote an extremely long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t show up. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyway, just wanted to say wonderful blog!

My spouse and I stumbled over here different web page and thought I might check things out. I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to looking over your web page yet again.

Прогон сайта с использованием программы “Хрумер” – это способ автоматизированного продвижения ресурса в поисковых системах. Этот софт позволяет оптимизировать сайт с точки зрения SEO, повышая его видимость и рейтинг в выдаче поисковых систем.

Хрумер способен выполнять множество задач, таких как автоматическое размещение комментариев, создание форумных постов, а также генерацию большого количества обратных ссылок. Эти методы могут привести к быстрому увеличению посещаемости сайта, однако их надо использовать осторожно, так как неправильное применение может привести к санкциям со стороны поисковых систем.

Прогон сайта “Хрумером” требует навыков и знаний в области SEO. Важно помнить, что качество контента и органичность ссылок играют важную роль в ранжировании. Применение Хрумера должно быть частью комплексной стратегии продвижения, а не единственным методом.

Важно также следить за изменениями в алгоритмах поисковых систем, чтобы адаптировать свою стратегию к новым требованиям. В итоге, прогон сайта “Хрумером” может быть полезным инструментом для SEO, но его использование должно быть осмотрительным и в соответствии с лучшими практиками.

Hi there, I found your web site by means of Google even as searching for a similar topic, your web site got here up, it looks good. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

You should take part in a contest for one of the highest quality sites on the internet. I will recommend this blog!

Хотите получить идеально ровный пол в своем доме или офисе? Обратитесь к профессионалам на сайте styazhka-pola24.ru! Мы предлагаем услуги по стяжке пола любой сложности и площади, а также устройству стяжки пола под ключ в Москве и области.

снабжение строительных объектов стройматериалами

Good day! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with SEO? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good results. If you know of any please share. Thank you!

Simply want to say your article is as amazing. The clearness in your post is simply cool and i can assume you are an expert on this subject. Well with your permission allow me to grab your RSS feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please keep up the rewarding work.

Hey! This is my 1st comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and tell you I genuinely enjoy reading through your articles. Can you suggest any other blogs/websites/forums that deal with the same subjects? Thank you so much!

Do you have a spam issue on this site; I also am a blogger, and I was wanting to know your situation; many of us have created some nice methods and we are looking to swap solutions with other folks, be sure to shoot me an e-mail if interested.

Hello there, You have done a fantastic job. I will definitely digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I am sure they will be benefited from this site.

Ощутите разницу с профессиональной штукатуркой механизированная от mehanizirovannaya-shtukaturka-moscow.ru. Процесс быстрый и чистый.

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information.

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it.

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

Great post thank you. Hello Administ .

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ .

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Hi my loved one! I want to say that this article is awesome, great written and come with almost all significant infos. I’d like to see more posts like this .

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it.

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ .

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ .

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

Thank you great post. Hello Administ .

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information.

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ .

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ .

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information.

Hey there just wanted to give you a quick heads up and let you know a few of the images aren’t loading correctly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different internet browsers and both show the same results.

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ .

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ .

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .

I seriously love your site.. Pleasant colors & theme. Did you create this web site yourself? Please reply back as I’m hoping to create my own website and want to know where you got this from or exactly what the theme is called. Many thanks!

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ .

I am extremely impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your blog. Is this a paid theme or did you customize it yourself? Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it’s rare to see a nice blog like this one nowadays.

인터넷카지노

이 순간 7, 8명의 지도자들이 흔들렸고, “이 개 황제를 쓰러뜨려라!”

Hello there, You have performed a fantastic job. I will definitely digg it and individually recommend to my friends. I am sure they will be benefited from this web site.

A person necessarily help to make significantly articles I might state. This is the first time I frequented your web page and to this point? I amazed with the research you made to create this actual post amazing. Great process!

Hongzhi 황제는 안도의 한숨을 쉬고 Xiao Jing을 응시했습니다. “이해합니다.”

씨큐나인슬롯

Thanks for your personal marvelous posting! I really enjoyed reading it, you might be a great author.I will always bookmark your blog and will eventually come back in the foreseeable future. I want to encourage continue your great writing, have a nice morning!

Can I just say what a relief to find somebody that truly knows what they’re talking about on the internet. You certainly know how to bring an issue to light and make it important. More and more people should read this and understand this side of the story. It’s surprising you aren’t more popular because you definitely have the gift.

Hey very interesting blog!

팀을 이끈 사령관은 Liu Jie를 발견하고 안도의 한숨을 쉬었습니다!

에그 슬롯

I visited many web sites but the audio quality for audio songs current at this site is really excellent.

It’s a shame you don’t have a donate button! I’d most certainly donate to this superb blog! I suppose for now i’ll settle for book-marking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account. I look forward to fresh updates and will talk about this site with my Facebook group. Chat soon!

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information. Website Giriş için Tiklatın : https://www.melekhali.com.tr/

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ .

Thank you great post. Hello Administ .

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ . Website : https://www.saricahali.com.tr/

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ . Website : https://www.saricahali.com.tr/

Oh my goodness! Awesome article dude! Thank you, However I am encountering difficulties with your RSS. I don’t know why I am unable to subscribe to it. Is there anyone else getting identical RSS problems? Anyone who knows the solution will you kindly respond? Thanx!!

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ.

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ .

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information.

Thank you great post. Hello Administ .

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ .

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ .

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it.

Thank you great post. Hello Administ . sollet sollet

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information. hdxvipizle hdxvipizle

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ . casinolevant casinolevant

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

you are actually a good webmaster. The web site loading velocity is incredible. It kind of feels that you are doing any unique trick. Moreover, The contents are masterpiece. you have performed a great task in this topic!

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ .

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ .

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it. Website : https://www.saricahali.com.tr/

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ. Website Giriş için Tiklatın : https://www.melekhali.com.tr/

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ .

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it.

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ .

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ . sollet sollet

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ . casinolevant casinolevant

Great post thank you. Hello Administ . sollet sollet

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ . bahis forum bahis forum

Good way of explaining, and good piece of writing to get information concerning my presentation subject, which i am going to deliver in academy.

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ . sollet extension sollet

하바네슬롯

그 Ouyang Zhi는 매우 정직한 사람처럼 보이지만 매우 정직하지만 …

Great post thank you. Hello Administ . venusbet venusbet

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it. venusbet deneme bonusu veren siteler

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ . türkçe altyazılı porno hdxvipizle

I am sure this piece of writing has touched all the internet viewers, its really really nice post on building up new blog.

Thank you great post. Hello Administ . bahis forum bahis forum

Great post thank you. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .Casibom Website Giriş : Casibom

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader. Casibom Website Giriş : Casibom

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ . Casibom Website Giriş : Casibom

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across. Casibom Website Giriş : Casibom

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ. Website : https://www.saricahali.com.tr/

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it. Website : https://www.saricahali.com.tr/

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ .

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across. Website : https://www.saricahali.com.tr/

Great post thank you. Hello Administ . Website : cami halısı

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ . Website : cami halısı

He appreciates when patients are their own advocate and know that they want to partner with him viagra for sale online

You’re so awesome! I don’t think I have read something like this before. So good to find somebody with a few unique thoughts on this subject. Really.. thank you for starting this up. This site is something that is needed on the web, someone with a little originality!

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ . Onwin , Onwin Giriş onwin

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across. Onwin , Onwin Giriş onwin

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ . Onwin , Onwin Giriş onwin

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it. Onwin , Onwin Giriş onwin

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ .

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ .

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information. Website : cami halısı

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ.

Thank you great post. Hello Administ .

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

베스트 슬롯 게임 플레이

“방금… 부자가 되라고 하셨습니까?” Zhang Heling의 눈이 빛났습니다.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ.

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ.

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it.

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader. Website : https://www.saricahali.com.tr/

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ.

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader. Onwin , Onwin Giriş onwin

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ . Casibom Website Giriş : Casibom

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.Onwin Giriş Website: onwin

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.Onwin Giriş Website: onwin

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .

Great post thank you. Hello Administ .

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ . Website : cami halısı

GlucoTrust is a revolutionary blood sugar support solution that eliminates the underlying causes of type 2 diabetes and associated health risks.

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ. Diyarbet , Diyarbet Giriş , Diyarbet Güncel Giriş , Diyarbet yeni Giriş , Website:

Great post thank you. Hello Administ . Diyarbet , Diyarbet Giriş , Diyarbet Güncel Giriş , Diyarbet yeni Giriş , Website:

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it. Diyarbet , Diyarbet Giriş , Diyarbet Güncel Giriş , Diyarbet yeni Giriş , Website:

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information. Diyarbet , Diyarbet Giriş , Diyarbet Güncel Giriş , Diyarbet yeni Giriş , Website:

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ . Diyarbet , Diyarbet Giriş , Diyarbet Güncel Giriş , Diyarbet yeni Giriş , Website:

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.Diyarbet , Diyarbet Giriş , Diyarbet Güncel Giriş , Diyarbet yeni Giriş , Website:

Diyarbet , Diyarbet Giriş , Diyarbet Güncel Giriş , Diyarbet yeni Giriş , Website:

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .Diyarbet , Diyarbet Giriş , Diyarbet Güncel Giriş , Diyarbet yeni Giriş , Website:

https://google.sk/url?q=https://www.pragmatic-ko.com/

이때 그의 심장은… 엄청난 충격을 받았습니다.

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .

Serolean a revolutionary weight loss supplement, zeroes in on serotonin—the key neurotransmitter governing mood, appetite, and fat storage.

Great post thank you. Hello Administ .

플레이앤고

주자이모가 말한 것은 사소한 일이었다.

Thank you great post. Hello Administ . Website : cami halısı

Elevate your vitality with Alpha Tonic – the natural solution to supercharge your testosterone levels. When you follow our guidance, experience improved physical performance

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ . Website : cami halısı

AquaPeace is the most in-demand ear health supplement on the market. Owing to its natural deep-sea formula and nutritious nature, it has become an instant favorite of everyone who is struggling with degraded or damaged ear health.

ProstateFlux™ is a dietary supplement specifically designed to promote and maintain a healthy prostate for male.

ReFirmance is an outstanding lift serum that highly supports skin firmness and elasticity, smooths the presence of wrinkles, and provides deep rejuvenation properties.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ .

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Website : cami halısı

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ .

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ .

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ.

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ .

Ощути вкус адреналина и брось вызов удаче с Лаки Джет на официальном сайте 1win. Быстро и легко – вот девиз игры Лаки Джет на деньги. Попробуй и убедись сам!

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ.

Great post thank you. Hello Administ .

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ . asyabahis asyabahis

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ . venusbet venusbet

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ . sahabet sahabet

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ . venusbet deneme bonusu veren siteler

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ . venusbet venusbet

SightCare supports overall eye health, enhances vision, and protects against oxidative stress. Take control of your eye health and enjoy the benefits of clear and vibrant eyesight with Sight Care. https://sightcarebuynow.us/

I was very pleased to find this site. I want to to thank you for your time just for this wonderful read!! I definitely loved every little bit of it and I have you book marked to check out new things on your blog.

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ . Website : cami halısı

https://www.michalsmolen.com

이때 Hongzhi 황제의 눈이 차가워졌습니다. “당신은 나를 비방합니까?”

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Thank you great post. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information.

SightCare supports overall eye health, enhances vision, and protects against oxidative stress. Take control of your eye health and enjoy the benefits of clear and vibrant eyesight with Sight Care. https://sightcarebuynow.us/

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ .

https://www.radiorequenafm.com

Xiao Jing은 몸을 떨며 즉시 “예, 예, 예 …”라고 말했습니다.

The most talked about weight loss product is finally here! FitSpresso is a powerful supplement that supports healthy weight loss the natural way. Clinically studied ingredients work synergistically to support healthy fat burning, increase metabolism and maintain long lasting weight loss. https://fitspressobuynow.us/

Boostaro is a dietary supplement designed specifically for men who suffer from health issues. https://boostarobuynow.us/

DentaTonic is a breakthrough solution that would ultimately free you from the pain and humiliation of tooth decay, bleeding gums, and bad breath. It protects your teeth and gums from decay, cavities, and pain. https://dentatonicbuynow.us/

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ .

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .

Thank you great post. Hello Administ .

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ .

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

Thank you great post. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information. Diyarbet

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ . Diyarbet

asyabahisgo1.com

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across. Diyarbet

seo paneli

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

pinbahis giriş

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ .

GlucoBerry is one of the biggest all-natural dietary and biggest scientific breakthrough formulas ever in the health industry today. This is all because of its amazing high-quality cutting-edge formula that helps treat high blood sugar levels very naturally and effectively. https://glucoberrybuynow.us/

EndoPump is a dietary supplement for men’s health. This supplement is said to improve the strength and stamina required by your body to perform various physical tasks. Because the supplement addresses issues associated with aging, it also provides support for a variety of other age-related issues that may affect the body. https://endopumpbuynow.us/

Endopeak is a natural energy-boosting formula designed to improve men’s stamina, energy levels, and overall health. The supplement is made up of eight high-quality ingredients that address the underlying cause of declining energy and vitality. https://endopeakbuynow.us/

GlucoFlush is an advanced formula specially designed for pancreas support that will let you promote healthy weight by effectively maintaining the blood sugar level and cleansing and strengthening your gut. https://glucoflushbuynow.us/

Kerassentials are natural skin care products with ingredients such as vitamins and plants that help support good health and prevent the appearance of aging skin. They’re also 100% natural and safe to use. The manufacturer states that the product has no negative side effects and is safe to take on a daily basis. Kerassentials is a convenient, easy-to-use formula. https://kerassentialsbuynow.us/

Illuderma is a serum designed to deeply nourish, clear, and hydrate the skin. The goal of this solution began with dark spots, which were previously thought to be a natural symptom of ageing. The creators of Illuderma were certain that blue modern radiation is the source of dark spots after conducting extensive research. https://illudermabuynow.us/

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information.Onwin Giriş için Tıklayın onwin

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .Onwin Giriş için Tıklayın onwin

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ . Onwin Giriş için Tıklayın onwin

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.Onwin Giriş için Tıklayın onwin

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across. Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ . Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .Onwin Giriş için Tıklayın onwin

Thank you great post. Hello Administ .Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ .

Great post thank you. Hello Administ . Onwin Giriş için Tıklayın onwin

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader. Onwin Giriş için Tıklayın onwin

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader. Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ. Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ . Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ . Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ . Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Thank you great post. Hello Administ .Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ. Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .Website Giriş için Tıklayın. Starzbet

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader. Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Thank you for great article. Hello Administ .Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Thank you great post. Hello Administ .Website Giriş için Tıklayın. Starzbet

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ . Website Giriş için Tıklayın. Starzbet

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it. Website Giriş için Tıklayın. Starzbet

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ . Website Giriş için Tıklayın. Starzbet

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across. Website Giriş için Tıklayın. Starzbet

Currently it looks like BlogEngine is the best blogging platform out there right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you’re using on your blog?

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ . Website Giriş için Tıklayın. Starzbet

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader. Website Giriş için Tıklayın. Starzbet

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ. Website Giriş için Tıklayın: tipobet

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.Onwin Giriş için Tıklayın onwin

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.Website Giriş için Tıklayın: tipobet

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ. Website Giriş için Tıklayın: tipobet

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ . Website Giriş için Tıklayın: tipobet

Great post thank you. Hello Administ . Website Giriş için Tıklayın: tipobet

I pay a visit day-to-day some web sites and information sites to read articles, except this weblog provides quality based content.

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ . Websiteye Giriş için Tıklayın. a href=”https://cutt.ly/SahabetSosyal/” title=”Sahabet” rel=”dofollow”>Sahabet

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it. Onwin Giriş için Tıklayın onwin

I really love to read such an excellent article. Helpful article. Hello Administ . Onwin Giriş için Tıklayın onwin

Great post thank you. Hello Administ . Website Giriş için Tıklayın. Starzbet

I am absolutely thrilled to introduce you to the incredible Sumatra Slim Belly Tonic! This powdered weight loss formula is like no other, featuring a powerful blend of eight natural ingredients that are scientifically linked to fat burning, weight management, and overall weight loss. Just imagine the possibilities! With Sumatra Slim Belly Tonic, you have the opportunity to finally achieve your weight loss goals and transform your body into the best version of yourself.

SeroLean is incredible supplement is specifically designed to help you manage your weight while also boosting your energy levels.

saungsantoso.com

그런데… 그렇게 거대한 차가 갑자기 진동하기 시작했다.

ProDentim – blend of essential nutrients, including vitamins C and D, calcium, and phosphorus, work in tandem with the probiotic strains to promote healthy teeth and gums. Vitamin C is essential for collagen production, which provides structure to teeth and gums, while vitamin D helps the body absorb calcium and phosphorus, which are crucial for healthy tooth enamel. Calcium and phosphorus are also important for maintaining strong teeth and bones, making ProDentim a comprehensive dental supplement that supports overall oral health.

Great post thank you. Hello Administ .

Hi, I think your blog might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your blog site in Chrome, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, wonderful blog!

Купить диплом цена https://kupit-diplom1.com/ — это шанс получить свидетельство быстро и легко. Сотрудничая с нами, вы приобретаете профессиональный документ, который соответствует всем требованиям.

Prostadine helps clear out inflammation in the prostate.Prostadine claims the root cause of most prostate issues is due to the accumulation of toxic mineral buildup due to hard water. When unchecked, this toxic buildup leads to inflammation in the prostate and the rest of your urinary tract. This impairs your ability to urinate, ejaculate, and produce hormones needed for your overall health.

Spot on with this write-up, I absolutely believe this web site needs a lot more attention. I’ll probably be back again to read through more, thanks for the info!

Discover Prostadine, your go-to supplement for maintaining optimal prostate health as you age. With nine natural ingredients dedicated to protecting and enhancing prostate well-being, this formula is your proactive solution for preventing issues and ensuring a healthy prostate as you grow older. Prioritize your prostate health with Prostadine for a vibrant, worry-free future.

Купить диплом техникумаhttps://kupit-diplom1.com/ — это вариант получить свидетельство быстро и легко. Сотрудничая с нами, вы приобретаете профессиональный документ, который полностью подходит для вас.

restaurant-lenvol.net

Liu Jin은 급히 밀랍 봉인을 열고 보고서를 꺼내 직접 열었습니다!

socialmediatric.com

지금은 법원에 너무 많은 제약이 있어서 그런 큰 일을 하는 것이 불가능하다.

Your posts are always so relevant and well-timed It’s like you have a sixth sense for what your readers need to hear

Sumatra Slim Belly Tonic is a unique weight loss supplement that sets itself apart from others in the market. Unlike other supplements that rely on caffeine and stimulants to boost energy levels, Sumatra Slim Belly Tonic takes a different approach. It utilizes a blend of eight natural ingredients to address the root causes of weight gain. By targeting inflammation and improving sleep quality, Sumatra Slim Belly Tonic provides a holistic solution to weight loss. These natural ingredients not only support healthy inflammation but also promote better sleep, which are crucial factors in achieving weight loss goals. By addressing these underlying issues, Sumatra Slim Belly Tonic helps individuals achieve sustainable weight loss results.

На нашем веб-сайтеhttps://diplomguru.com каждый клиент может приобрести диплом колледжа или университета по своей специализации по очень низкой цене.

It’s clear that you truly care about your readers and want to make a positive impact on their lives Thank you for all that you do

Glucotrust is a revolutionary nutritional supplement that is designed to support healthy blood sugar levels in the body. It is made from a blend of essential nutrients and powerful antioxidants that work together to promote optimal health and wellness.

Hi there I am so grateful I found your weblog, I really found you by mistake, while I was researching on Google for something else, Anyhow I am here now and would just like to say thank you for a marvelous post and a all round enjoyable blog (I also love the theme/design), I dont have time to browse it all at the minute but I have saved it and also included your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read a great deal more, Please do keep up the awesome b.

Sugar Defender transcends symptom-focused interventions, delving into the root causes of glucose imbalance. It stands as a dynamic formula that seamlessly aligns with the body’s intrinsic mechanisms, presenting a distinctive and holistic approach to enhancing overall well-being. Beyond a mere supplement, Sugar Defender emerges as a strategic ally in the pursuit of balanced health.

This post hits close to home for me and I am grateful for your insight and understanding on this topic Keep doing what you do

Заинтересованы в доставке диплома быстро и без излишних заморочек? В Москве предоставляется обилие возможностей для приобретения диплома о высшем образовании – diplom4.me. Специализированные агентства оказывают помощь по приобретению документов от различных учебных заведений. Обращайтесь к надежным поставщикам и добудьте свой диплом уже сегодня!

agonaga.com

Wang Shouren은 몇 명의 오래된 장인을 따라 목재 가구를 칠했습니다.

It’s really a nice and helpful piece of information. I’m satisfied that you shared this helpful info with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

Your writing is so eloquent and heartfelt It’s impossible not to be moved by your words Thank you for sharing your gift with the world

Alpilean is an Industry-Leading Weight Loss Support Supplement taking the market by storm. 100% Natural Ingredients are used in the making of the Supplement.

rivipaolo.com

이 순간 모두의 시선이 팡지판에게 쏠렸다.

Red Boost is a powerful and effective supplement that is designed to support overall health and well-being, particularly in men who may be experiencing the signs of low testosterone. One of the key factors that sets Red Boost apart from other supplements is its high-quality and rare ingredients, which are carefully selected to produce a powerful synergistic effect. Here is a list of the key ingredients in Red Boost and how they can support overall health and well-being:

Fluxactive is a comprehensive dietary supplement made up of herbal extracts. This supplement is high in nutrients, which can properly nourish your body and significantly improve prostate health. Some of these ingredients have even been shown to lower the risk of prostate cancer.

Закупка диплома в городе diplomsuper.net становится все все более и более известным решением среди тех, кто, кто стремится к быстрому и удобному приобретению публичного образовательного аттестата. В столице предоставляются различные услуги по приобретению дипломов разных уровней степени и специализаций специализации.

For the reason that the admin of this site is working, no uncertainty very quickly it will be renowned, due to its quality contents.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

I am truly thankful to the owner of this web site who has shared this fantastic piece of writing at at this place.

this-is-a-small-world.com

그러자 그는 갑자기 눈을 뜨고 떨리는 목소리로 말했다. “가게 주인 왕, 농담하지 마세요.”

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it.

Thank you great post. Hello Administ .

Приобрести свидетельство института: Приобретение диплома высшего уровня образования поможет вам продвинуться на новый уровень квалификации в деле.

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ .

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ .

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information.

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ. venusbet venusbet

В Москве купить свидетельство – это удобный и экспресс метод получить нужный запись лишенный дополнительных трудностей. Большое количество компаний продают сервисы по производству и реализации свидетельств разных образовательных учреждений – https://www.diplomkupit.org/. Ассортимент свидетельств в столице России огромен, включая документация о высшем уровне и среднем ступени образовании, документы, свидетельства техникумов и академий. Главное достоинство – возможность достать свидетельство Гознака, обеспечивающий достоверность и качество. Это предоставляет особая защита ото фальсификаций и предоставляет возможность воспользоваться свидетельство для разнообразных целей. Таким способом, заказ диплома в городе Москве становится надежным и оптимальным выбором для данных, кто хочет достичь успеху в сфере работы.

Pretty! This has been a really wonderful post. Many thanks for providing these details.

This blog post has left us feeling grateful and inspired

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it.

It means so much to receive positive feedback and know that my content is appreciated. I strive to bring new ideas and insights to my readers.

Nice article inspiring thanks. Hello Administ .

Купить свидетельство – это возможность скоро получить запись об академическом статусе на бакалавр уровне без дополнительных хлопот и затраты времени. В Москве доступны множество вариантов подлинных свидетельств бакалавров, гарантирующих комфорт и удобство в процессе.

Sugar Defender orchestrates a reduction in blood sugar levels through multifaceted pathways. Its initial impact revolves around enhancing insulin sensitivity, optimizing the body’s efficient use of insulin, ultimately leading to a decrease in blood sugar levels. This proactive strategy works to prevent the storage of glucose as fat, mitigating the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Hi there to all, for the reason that I am genuinely keen of reading this website’s post to be updated on a regular basis. It carries pleasant stuff.

very informative articles or reviews at this time.

I’m often to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has actually peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your web site and maintain checking for brand spanking new information.

I’m often to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has actually peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your web site and maintain checking for brand spanking new information.

Good post! We will be linking to this particularly great post on our site. Keep up the great writing

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Thank you for great information. Hello Administ .

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information.

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information. asyabahis asyabahis

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ .

Thank you great post. Hello Administ .

Great post thank you. Hello Administ .

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across.

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ.

Thank you great posting about essential oil. Hello Administ . betforward betforward1.org

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ .

Great post thank you. Hello Administ .

this-is-a-small-world.com

물론 그는 감히 보여주지 않았고 그의 선생님이 가르친 것은 과시하지 않고 낮은 프로필을 유지하는 것이 었습니다.

Thank you for content. Area rugs and online home decor store. Hello Administ .

Thank you for great content. Hello Administ.

olabahis

This is my first time pay a quick visit at here and i am really happy to read everthing at one place

I do not even understand how I ended up here, but I assumed this publish used to be great

Nice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on websites

Hi there to all, for the reason that I am genuinely keen of reading this website’s post to be updated on a regular basis. It carries pleasant stuff.